“I know a lot about structural variation information,” but the content of this blog post is too much, and it’s not convenient for me to look back. So I decided to split it into smaller parts and write a comprehensive one using GitBook later.

Structural Variations/Copy Number Variations/Gene Fusions

Structural variations are different from small-scale gene mutations like SNPs/InDels, referring to all relatively large-scale gene mutations (the exact size threshold is not clearly defined). Most literature refers to these variations as structural variations (Structural Variation), which are believed to originate from chromosomal reorganization or rearrangement. These variations come in various sizes and styles, ranging from whole chromosome exchanges mentioned in biology class to simple segment deletions, which are just relatively larger segments.

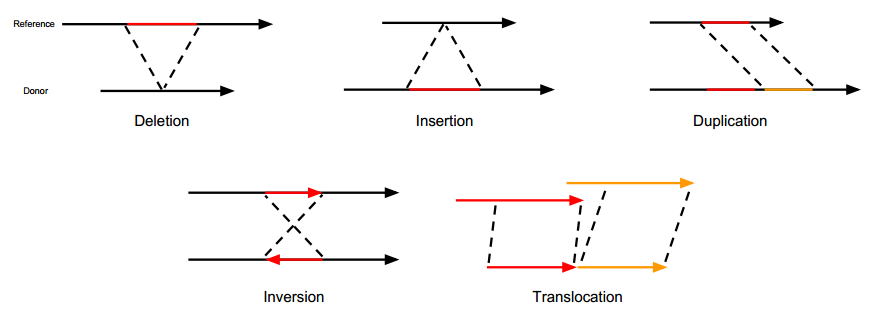

Currently, structural variations are mainly classified into the following types:

- Insertion/Deletion (Insertion/Deletion, INS/DEL): Essentially the same as InDel but with larger fragments.

- Duplication (Duplication, DUP): Represents the continuous repetition of a certain region. Additionally, there is ‘tandem duplication’, which requires further investigation.

- Inversion (Inversion, INV): The 5’ and 3’ ends of a chromosomal segment are reversed.

- Translocation (Translocation, ITX, CTX): Refers to the transfer of a segment, which could be within the same chromosome or between different chromosomes. Translocations themselves are complex structural variations. For example, if a segment from position A on a chromosome is moved entirely to position B, then there will be a deletion at position A and an insertion at position B. If the inserted segment is not inserted in its original direction, then inversion also occurs.

The following image is taken from Gawroński’s doctoral thesis and vividly illustrates the types of structural variations.

Based on structural variations, we can further explore copy number variations (Copy Number Variation) and gene fusions (Gene Fusion).

The key to copy number variation is ‘copy’. For example, ‘ATGCGGTAGCCGTAT’ represents a complete gene sequence, which we call one copy. Since humans are diploid, normally there should be two copies of this gene in a person. Therefore, when detecting genes, if the number of copies of this gene in the genome is not 2, we say that a copy number variation has been detected.

From the above concept, we can see that copy number variation is essentially a structural variation or more precisely, a result of structural variation. If there is a deletion in the genome, then the number of gene copies must decrease. Duplication obviously leads to an increase in copy numbers. Why are copy number variations singled out? I personally think this may be related to when the concept was proposed or its underlying significance. Assuming each different copy of the gene has the same expression capacity, then an increase in gene copy numbers will inevitably lead to increased gene expression, while a decrease in copy numbers will result in decreased gene expression or even disappearance of related expression products. In short, compared to structural variations that focus on figuring out what kind of changes occurred in a gene segment (such as where the deleted segment starts and ends, whether it has moved to another location in the genome, etc.), copy number variations focus more on whether the copy number of a certain gene/segment has changed. Due to different focuses, copy number variations can be detected together with structural variations or separately. In fact, most of the time they are detected separately using different strategies. This article mainly focuses on structural variations, so there will not be specific content about copy number variations.

Similarly, gene fusions (Gene Fusion) are also results of structural variations. For example, if a segment of a gene is completely deleted, then the upstream and downstream segments will inevitably connect. If the breakpoints before and after the missing segment happen to be in the expression regions of two genes, then these two genes will be connected together, which is gene fusion. Therefore, we can see that all structural variations may lead to gene fusions, but the final way they fuse is different. Gene fusions are of particular interest because they are involved in confirming some disease causes. For example, EML4-ALK fusion in cancer and BCR-ABL fusion in chronic myeloid leukemia. Since gene fusions focus on whether there are genes connected together and how they connect (which affects whether gene expression increases or decreases), they have specific strategies and tools for detection, which will be detailed later.

Using NGS Data to Detect Structural Variations/Gene Fusions

The basic principle of second-generation genome resequencing is to break the complete gene sequence into fragments, then sequence these fragmented sequences and align them back to the reference genome to reconstruct the original sequence. During this alignment process, some “abnormal” alignment results will be produced. Among these results, some can indicate that the test genome has undergone structural variations relative to the reference genome, and our detection is based on these alignment results, which we call structural variation signals/evidence.

Structural Variation Detection Strategies

The basic strategies for detecting structural variations are generally classified into four categories:

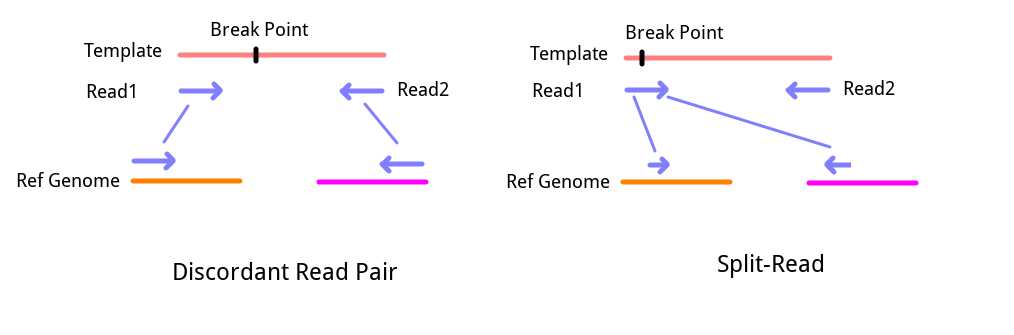

1. Split-Reads

If you have ever worked with NGS sequence alignment files (SAM/BAM), you must have seen Clip-Reads in the file. Simply put, these sequences cannot be fully aligned to a specific location on the genome during alignment and instead align partially to one place and partially to another. These sequences may come from fragments containing structural variation breakpoints, thus resulting in this abnormal “chimeric alignment“. By extracting these sequences and tracing back the alignment of the two clipped sequences, we can infer the type of structural variation to some extent. The strategy for detecting structural variations based on this information is called SR strategy.

2. Discordant Read Pairs

If paired-end sequencing (Pair-End Sequencing) was used, then the sequencing results will appear in pairs. According to the sequencing principle, paired-end sequencing yields a single DNA strand’s 5’ and 3’ sequences. Since the DNA library preparation breaks DNA into a fixed range, under normal circumstances, the distance between Read1 and Read2 on the genome should be within a fixed range, and one should align positively with the reference genome while the other should align negatively (complementary). However, in actual alignment results, there will always be some sequence pairs that do not meet these conditions, such as a large distance or even different chromosomes, or both Read1 and Read2 aligning positively on the genome. In this case, these sequences are called “Discordant Read Pairs”. Since this signal comes from a pair of sequences, it is directly referred to as “Pair-End Evidence, PE” in Lumpy, but based on this signal, detection strategies seem to be more frequently called RP (Read Pair) strategy (this needs further confirmation by reading more evaluation articles). Such read pairs may also come from fragments containing structural variation breakpoints. The difference lies in the position of the breakpoint. For Split-Reads, the breakpoint is at one end of the sequence, so it is detected directly. For Discordant Read Pairs, the breakpoint should be within the insert fragment range, meaning it is not directly reflected in the sequenced fragments.

3. Read Count or Depth

This strategy is based on the sequencing depth of specific segments. Clearly, this is used to detect copy number variations. Regardless of what kind of structural variation occurs, if it ultimately results in a decrease in the number of copies of a gene, it should be intuitively reflected in the alignment results of that gene—i.e., the sequencing depth of that gene region will clearly decrease. Conversely, if there is an increase in copy numbers, the sequencing depth should also correspondingly increase. This strategy is theoretically simple from a principle standpoint, but it is not necessarily much simpler than the previous two strategies in actual application. The main issue it faces is a seemingly simple but very troublesome problem: how high does the depth need to be considered significantly high, and how low does it need to be considered significantly low? This problem becomes more complex when using targeted or exome sequencing for copy number variation detection.

4. De novo Assembly

Here, de novo assembly refers to assembling the genome from scratch without relying on a reference sequence, which is essentially the same as second-generation sequencing. Applied in structural variation detection, it involves assembling the obtained sequences before looking for SR or PE signals. Since assembled sequences yield longer fragments, these fragments can be used for better alignment results. It can be seen that this AS strategy will not be used alone because its purpose is to obtain longer fragments and then re-align them before detecting using SR.

Personal Thoughts on Detection Strategies

1. Theoretical and Practical Aspects of Sequencing Methods

As mentioned in Professor Huang Shujia’s blog post, to obtain more reliable structural variation detection results, increasing fragment length and performing whole-genome sequencing is the simplest direct method. However, both methods mean increased single-test costs. Until sequencing becomes truly affordable, using as little data as possible to achieve more reliable results will be a necessary problem in applying structural variation detection in clinical settings.

2. Difficulty of Obtaining PE and SR Signals

Assuming that the possibility of a structural variation breakpoint being sequenced is equal, then obtaining PE signals should be greater than obtaining SR signals because the length of insert fragments is usually longer than the reads themselves, so more breakpoints will fall within the insert fragment range. Additionally, since most detection methods still rely on alignment, some SR signals may also lose due to poor breakpoint positions (too close to read ends), making correct alignment difficult and causing signal loss. Therefore, under the same sequencing depth, applying PE signals theoretically can improve detection sensitivity.

3. Detection Bottlenecks Caused by Alignment

Since most tools still rely on sequence alignment situations, if real variation signals exist but are difficult to align (sequences too short for alignment), some signals will inevitably be lost and affect detection accuracy. This has also led to attempts at non-alignment-based detection methods.

Gene Fusion-Specific Detection Strategies

As mentioned earlier, gene fusion is a result of structural variation. Some gene fusions are of interest because they lead to abnormal gene expression, resulting in diseases. Therefore, in gene fusion detection, the focus is on detecting whether genes have fused together and how they have fused. Due to this different focus, besides using structural variation detection strategies to detect structural variations from the genome and then interpret possible fusions, specialized fusion detection methods have also been developed: RNA-Seq fusion detection. This method directly detects fusions in the transcriptome. If sequences from different gene transcripts are detected, it indicates a gene fusion event. Additionally, since detecting is done with RNA, there’s no need to speculate whether fusion will occur because detecting it proves its effectiveness.

Of course, I don’t think this method is perfect either. Some potential drawbacks include:

- Higher detection difficulty compared to DNA, as RNA is easily degraded…

- As an applied clinical testing method, using RNA testing should have sample limitations and cost constraints.

Since I haven’t used such tools in my actual work yet and don’t plan to use them, I’ll come back to fill this pit later.

Additionally, most current structural variation/fusion detection methods require alignment to a reference genome, which is currently time-consuming (except for using FPGA chips for specialized optimization). However, gene fusion essentially only needs to know whether there are sequences showing two genes fused together. Therefore, some commercial companies have developed non-alignment-based detection schemes based on fastq data (such as [GeneFuse by Shenzhen Haplos]), which indeed significantly speeds up the detection process.

Finally, one thing to note is that due to different focuses, some specialized gene fusion detection software only reports fused genes and specific exons in their results, in various forms, making it difficult to directly compare with structural variation detection tools.